| Conditions: Food and Agriculture |

|

Like the rest of this website,

the following section reflects impressions mixed with occasional

facts gained in several weeks of traveling by bike -- not

systematic research. That said, what kind of conditions did

we see in Cuba in 2000? We'll look at food, housing, medicine,

and education.

|

|

|

With

the end of Soviet aid and the collapse of the economy in the

early 90's, food became scarce, and many Cubans went hungry.

Things are somewhat better now. As far as we could see, malnutrition

in 2000 was nonexistent, though Cubans without access to U.S.

dollars still struggle. With

the end of Soviet aid and the collapse of the economy in the

early 90's, food became scarce, and many Cubans went hungry.

Things are somewhat better now. As far as we could see, malnutrition

in 2000 was nonexistent, though Cubans without access to U.S.

dollars still struggle.

For tourists, food was not a problem,

though meals tended to be monotonous. We also found food to

be quite safe. Some kitchens looked dingy, but that was probably

the result of a years of shortages of cleansers and paint. We

always ate salads, raw fruit, and snacks from roadside vendors

without significant health problems over two months.

Water was a different matter.

We were warned many times that water treatment in towns and

cities was unreliable, and we met many Cubans who boil their

drinking water or use water treatment tablets (when they can

get them.) Barbara got quite sick, almost certainly from bad

water, on our first trip in 1999. In 2000, therefore, we brought

a water filter and used it regularly, and we bought a great

deal of bottled water (and good beer!) as well.

|

|

Without doubt, one eats better

in private homes, casas particulares, than in moderately-priced

hotels or restaurants. Your hosts use your U.S. dollars to buy

extra food for you -- and for themselves -- in the free market.

Meals are generally based on chicken, pork, or fish, served

with congris -- beans and rice -- and various vegetables and

salads. Our Cuban hosts invariably put a great deal of effort

into making meals attractive and appetizing.

|

|

|

Still, there's an old joke in

Cuba: The three great successes of the revolution have been

medicine, education, and sport; the three great failures have

been breakfast, lunch, and dinner. This is a huge feedlot outside

Havana. It seemed to go on for miles. And it was completely

abandoned. We don't know if this resulted from lack of inputs

owing to the economic collapse of the 1990's -- or just bad

planning.

|

|

Some people told us that large

scale, collective agriculture in Cuba, as represented by the

defunct feedlot, simply doesn't work well. What does seem to

work, they said, is production by smallholders. Since 1994,

peasant farmers have been allowed to sell part of their production

in public markets for their own profit, and this has improved

the availability of food considerably.

|

|

|

We saw intensively-cultivated

gardens like this all over the country, especially outside the

big, soviet-style apartment blocks that ring some of the cities.

|

|

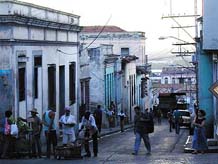

A lot of the produce from these

gardens is rolled into the city centers on wheelbarrows or hauled

in carts and sold in the streets for pesos, as here in Santiago

de Cuba. Traveling by bike, we very often made meals of fruit

and other foods that we bought from street vendors.

|

|

|

We were taught the saying, "Sin

sucre, no hay pais," without sugar, there is no country. We

were in Cuba during the months of the sugar harvest. Much of

the work was done with big machines -- but some of the cane

was still harvested by hand, and the less mechanized approach

was more photogenic.

|

|

Tobacco is also important to the

economy. The best tobacco comes from Pinar del Rio province,

and all the tobacco we saw appeared to be grown by small-scale

farmers. This farm is in the Vinales Valley. Leaves were dried

for a few days in the sun, then cured in the shade of the thatched

building.

|

|

|

Cuban cigars are still rolled

by hand, and it is skilled work. We were interested to see that

Cuban cigar factories still employ "readers." At the front of

the room, someone reads aloud from newspapers, short stories,

even novels, to help workers pass the time and further their

education as well.

|

|